Have you ever been prescribed hormonal birth control for heavy periods, painful periods, or lack of periods altogether? Each of these reproductive issues may originate with a problem during the first half, or follicular phase, of the menstrual cycle–issues that birth control unfortunately does nothing to treat.

Recently in our “FAM Basics” series we covered estrogen, ovulation, and cervical mucus, and in this article we’ll tie those topics together with a deep dive into the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, the part of the cycle that begins with menstruation and continues through the rise in estrogen leading to ovulation. We’ll explore what normally happens during the follicular phase as well as what can go wrong, and how to find answers beyond the Band-Aid solution of hormonal birth control.

The menstrual cycle has two phases: follicular and luteal

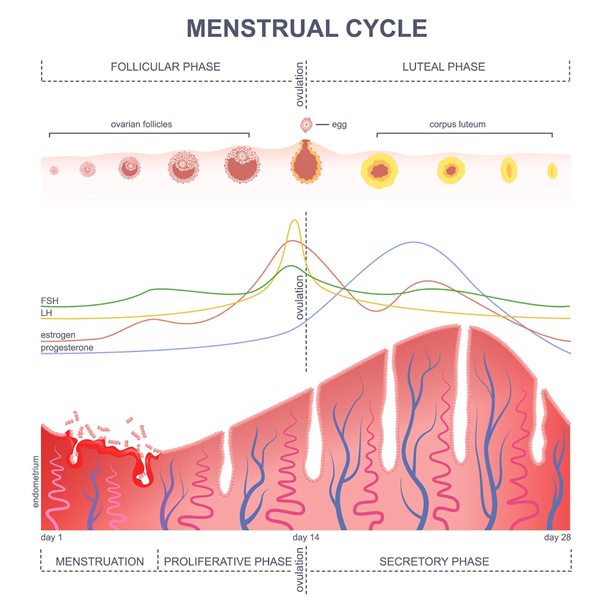

The menstrual cycle has two distinct phases: the follicular phase and the luteal phase. An easy way to remember the correct order is to recall that “the follicle comes first.”

The follicular phase begins with menstruation and ends with ovulation, and the luteal phase begins after ovulation and continues through the end of the cycle, ending on the last day before menstruation begins again. The follicular phase sees the significant rise of estrogen, FSH, and LH, while progesterone is the dominant hormone in the luteal phase.

What’s supposed to happen during the follicular phase?

Menstruation

Menstruation, or your “period,” is the shedding of your uterine lining, known as the endometrium, which was built up during your previous cycle. A healthy menstrual period lasts three to seven days, with medium or heavy bleeding (three or more pads or tampons per day) occurring on at least one of those days. Spotting before one’s menstrual flow begins could be indicative of endometriosis, a condition in which tissue similar to endometrial tissue grows outside of the uterus.

According to Period Repair Manual by naturopathic doctor Lara Briden, in addition to blood, menstruation also contains cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, and uterine tissue. Briden notes that some women, especially those with heavy periods, may experience a few clots, but they should be about the size of a dime. Heavy periods with lots of clots can be indicative of a few common reproductive disorders (more on that in a bit!).

Follicle maturation

Early in the follicular phase, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) directs several eggs, each contained in a sac called a follicle, to grow inside the ovaries. One egg becomes dominant and matures fully. The follicle of the dominant egg starts to produce estrogen, which then stimulates the release of large amounts of luteinizing hormone (LH). In turn, LH tells the dominant follicle to release the mature egg. This release process is called ovulation. Ovulation occurs about 24 to 36 hours after the rise of LH, which is known as the LH surge.

Observable signs (aka biomarkers) of the follicular phase

Observing signs like cervical mucus and hormone levels can help a woman monitor her health and achieve or avoid pregnancy. These signs are known as biomarkers, and they can clue a woman into what’s going on during each phase of her cycle.

A woman who diligently charts her cycle can observe several biomarkers during the follicular phase, including cervical mucus, basal body temperature, and hormonal fluctuations (via hormone test strips and/or monitors). Some women may also see some spotting (very light bleeding) around ovulation.

Cervical mucus

At first, many women may experience several days of dryness after menstruation, while both estrogen and progesterone levels are low. On the other hand, women with shorter overall cycles or longer periods may start to observe cervical mucus as soon as their periods end.

As ovulation approaches and estrogen levels rise, the cervix secretes a slippery clear or egg white-appearing fluid called estrogenic mucus. Women may observe this fertile mucus as a moist or lubricative sensation or may see it on the tissue as part of going to the bathroom. After intercourse, this fertile mucus helps transport sperm to reach the egg so that conception can occur.

Basal body temperature

A woman charting her basal body temperature as part of a symptothermal method will typically see a steady, lower temperature during the follicular phase. She will observe a significant temperature change after ovulation, during the beginning of the luteal phase.

Hormone monitors

Urine hormone tests such as at-home LH and estrogen tests can help identify impending ovulation for women who use symptohormonal methods of fertility awareness.

How long does the follicular phase last?

Between the two phases of the hormonal cycle, follicular phase length is in the driver’s seat when it comes to determining overall cycle length. Unlike the luteal phase, which is typically very stable in length, follicular phase length can vary considerably based on multiple factors that impact when the brain releases FSH (called FSH launch).

For example, many women may observe a longer follicular phase and therefore delayed ovulation when they are ill or under a lot of stress. When a woman has an abnormally long cycle, meaning one that’s longer than 36 days, it’s generally due to delayed FSH launch. A shorter than normal cycle, one lasting less than 24 days, may be because of a deficient luteal phase related to hormonal imbalances, or because of a shorter follicular phase due to early FSH launch. In other words, if you have an “irregular period,” it’s because ovulation is irregular!

Problems originating in the follicular phase

Not ovulating (anovulation)

It is possible to experience anovulatory cycles—cycles in which ovulation does not occur. An anovulatory cycle is caused by low estrogen and progesterone, though there may still be enough estrogen to stimulate enough growth of the endometrium to have a bleed. (Note: For bleeding to be a true menstrual period, it must be preceded by ovulation, hence why we do not refer to bleeding during anovulatory cycles as a period.)

Consistently anovulatory cycles can increase a woman’s risk of ovarian cancer and bone mineral loss. Possible causes of anovulatory cycles include polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), recent use of the birth control pill, and stress. Anovulatory cycles are normal and expected early in puberty, while breastfeeding, and during perimenopause.

It’s possible to have consistent or “regular” bleeds without ovulating, which is one reason why it’s important for women to chart their cycles. If a woman is having regular bleeding but is not observing other signs of ovulation (i.e., fertile cervical mucus, an LH surge, and/or a rise in temperature), she may be experiencing anovulatory cycles. A restorative reproductive health provider, such as one trained in NaPro or FEMM, can confirm if this is the case, and then identify the right treatment approach.

Not having a period (amenorrhea)

Amenorrhea is a term used when a woman doesn’t have a period. It can occur due to stress, illness, trauma, surgery, undereating, or medical conditions such as celiac disease or thyroid disease, according to Dr. Briden’s book. Amenorrhea can also occur in women with PCOS. Not having a period is a cause for concern, as it likely means you are not ovulating, which is essential for a woman’s health. In fact, periods are necessary for brain, heart, bone, and immune health, as described in this short video.

Heavy periods (menorrhagia)

Briden defines a heavy period as blood loss of more than 80 milliliters or almost three ounces, which is roughly equivalent to changing your pad or tampon more frequently than once every one to two hours. Bleeding for more than seven consecutive days would also constitute a heavy period. Heavy bleeding can be caused by the copper IUD, perimenopause, anovulatory cycles, thyroid disease, coagulation disorders, endometriosis, and adenomyosis (a condition in which tissue similar to endometrial tissue grows within the muscles of the uterus).

Painful periods (dysmenorrhea)

Minor discomfort before menstruation and around the time of ovulation is common. Minor cramping right before the beginning of menstruation or in the first couple days of menstruation is normal. In contrast, dysmenorrhea, or severe pain during menstruation that is not relieved with ibuprofen and interferes with a woman’s life, is less common and is not normal. Dysmenorrhea is often due to a hormonal imbalance or a condition like endometriosis, adenomyosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, or uterine fibroids.

Similarly, as Dr. Briden writes in The Period Repair Manual, minor pain with ovulation (often called mittelschmerz) is normal and “feels like a little twinge in your lower pelvis.” This pain should be brief and not require a painkiller. More severe pain may be due to PCOS, endometriosis, adenomyosis or an ovarian cyst or infection. Lack of periods, heavy bleeding, dysmenorrhea, and severe pain around the time of ovulation all merit further investigation from a healthcare professional trained in restorative reproductive medicine.

The importance of learning to chart your cycle

Identifying follicular phase problems in women who don’t know how to chart their cycles can be very challenging. Even when a woman and her healthcare provider do identify issues, thorough charting is often vital for correctly making a diagnosis and creating an appropriate treatment plan. Learning to chart a fertility awareness method with the help of an instructor trained in that specific method helps women better understand their bodies and improve their reproductive as well as overall health.

Additional Reading:

Cycle Syncing: How to Hack the Normal Hormonal Shifts of Your Cycle

5 Ways Stress Can Affect Your Period and the Rest of Your Cycle