Pregnancy is hard, and it always will be. But, thanks to modern medicine, pregnancy should be life-making and not life-taking. Unfortunately, in America, maternal mortality rates have been increasing since the 1980s, according to the CDC. Further, America’s maternal crisis reveals racial disparities, as black women and Native American women are about three times as likely to die from delivery complications as white women, a disparity that holds across all education and socioeconomic levels.

In April 2016, one such woman who died was Kira Johnson. Johnson had a happy home with her husband Charles and son Charles Jr. She also had a pilot’s license and fluency in five languages. But she didn’t have the care she needed to survive complications of childbirth. After giving birth via planned C-section, doctors and nurses failed to notice an internal hemorrhage for hours and ignored her husband Charles Johnson’s calls for help. When they finally took Kira back to surgery, it was too late.

“There’s nothing that can prepare you for what it’s like when your child wants to know why mommy isn’t coming home,” Johnson told CNN.

The CDC defines a pregnancy-related death “as the death of a woman while pregnant or within one year of the end of a pregnancy—regardless of the outcome, duration or site of the pregnancy—from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.”

According to global health data, the United States ranks poorly among developed nations in its maternal mortality rate. In 2018, the United States saw more maternal deaths than lower-income countries like Bosnia, Iran, Qatar, Korea, and Uruguay. According to an NPR report on the death rate of black American mothers, “the disproportionate toll on African-Americans is the main reason the U.S. maternal mortality rate is so much higher than that of other affluent countries. Black expectant and new mothers in the United States die at about the same rate as women in countries such as Mexico and Uzbekistan, the World Health Organization estimates.” Although not all countries use the same criteria as the United States in defining pregnancy-related deaths up to one year postpartum, the United States still has a lot of room to grow in improving this critical aspect of women’s health.

A fuller view of women’s health

“We really need to work to make pregnancy and childbirth safer,” Dr. Summer Holmes-Mason, OB/GYN, told us in an interview. “Already there are a lot of people who have efforts toward pregnancy prevention, but we need to work to make pregnancy and childbirth safer, as well as that fourth trimester period, that period after childbirth as women are transitioning to motherhood.”

For Holmes-Mason, the maternal mortality crisis “seems to be a multifactorial problem—some of it is resulting from systems-based issues such as coordination of care outside hospitals, from an inpatient setting to a primary care setting for issues they may have, such as hypertension or something that could increase the risk for cardiovascular disease.” Holmes-Mason explains that “women at risk for chronic conditions such as hypertension can lead to cardiomyopathy for example, which is a cause of heart failure—a fairly large contributor to loss of life for women postpartum.” Of course, Holmes-Mason adds, “some people may seem to have no risk factors and still things can go awry, and that’s where the acute initiatives for things in hospitals like identifying postpartum hemorrhage, identifying preeclampsia; those are going to be imperative, and those initiatives are working for sure.”

“But the other systems-based issues would be system biases more applicable to the ethnic disparities we see in our country,” Holmes-Mason says. “We know that black American women are more likely to die, but they’re also more likely to die in particular from postpartum hemorrhage as well as these cardiovascular events. And there are many institutions that have already taken action to identify postpartum hemorrhage earlier to initiate treatment earlier so that moms aren’t neglected,” Holmes-Mason says. “But I think, for women of color, often their concerns aren’t heard, probably because of some implicit bias. And the research really shows that it’s not just physiology, but that there are prejudices we have.”

If medical professionals discount the concerns raised by black patients and their caretakers, the results can be fatal. Holmes-Mason said perhaps some nurses or doctors may have in their mind a caricature of an “angry black women” or think black patients are “being dramatic,” or otherwise have perceptions that contribute to viewing such patients’ concerns as not founded—“but oftentimes they are, and they might not be evaluated as quickly as those who look differently; they may not be taken as seriously and addressed as early from the get go” as patients who aren’t black.

In addition to these biases, Holmes-Mason says there are other factors that contribute to our maternal mortality crisis, such as rarer conditions, “like amniotic embolism, which is harder to do research on because it’s so rare. So that’s one of the challenges, too.”

C-section would also be a risk factor, Holmes-Mason adds, “because women are more likely to have health complications from C-section compared to vaginal delivery.” While it’s a work in progress, Holmes-Mason says, “several organizations have taken measures, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), together with the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) and a group called AIM (Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health)—they are working to coordinate care measures and maternal safety initiatives, such as reducing primary cesarean section, and reducing racial disparities.”

The postpartum period is just as dangerous as childbirth

While the CDC’s definition of pregnancy-related deaths including up to a year postpartum may seem like a liberal definition, a consequence of this definition is the spotlight it places on postpartum maternal health. In 2018, 658 women died within six weeks (42 days) of childbirth, according to the CDC’s report on National Vital Statistics. On average, the CDC estimates that 700 women die each year from pregnancy or delivery complications. The CDC also estimates that as many as 60% of pregnancy-related deaths could be prevented, and that 1 in 3 pregnancy-related deaths actually occur during the postpartum period (from 1 week to 1 year after childbirth).

According to research compiled by the Nine Maternal Mortality Review Committees, the highest risk for pregnancy-related death occurs within six weeks of the end of pregnancy (45.0%), even more so than during pregnancy (37.6%) or 43 days to one year after the end of pregnancy (17.5%). The Nine Committees found seven leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths, including: Hemorrhage (14%), cardiovascular and coronary conditions (14%), infection (10.7%), cardiomyopathy (10.7%), embolism (8.4%), preeclampsia and eclampsia (7.4%), and mental health conditions (7.0%). Again, with proper provider awareness and medical management, many of the deaths due to these underlying causes are preventable.

Given these statistics, it is a scandal that we have virtually nonexistent postpartum care in the United States. An American woman’s postpartum care typically consists of a single follow-up appointment 6 weeks after childbirth. While ACOG now recommends that postpartum care should be an ongoing process—rather than a single encounter—and that all women have contact with their OB/GYNs or other obstetric care providers within the first three weeks postpartum, there is a long way to go in implementing these recommendations and cultivating a more comprehensive postpartum care mentality.

Consider the current paradigm: The prenatal period is full of dozens of checkups, and newborn babies and infants will have several checkups within the first six months of life. But for most mothers, one postpartum checkup at six weeks is all that is recommended (or covered by insurance). The message this sends is so loud as to be deafening: Mom’s health doesn’t matter. Is it any wonder that especially amidst the all-encompassing stress of new motherhood, slightly fewer than half of postpartum women make or keep their postpartum appointments?

“Traditionally a woman would be discharged in the hospital and we’d see her at 6 weeks. And a lot can happen in that time period,” Holmes-Mason says. From her view, improving healthcare in the postpartum period involves “taking the time to see her more often between then,” whether in person or by phone; and “striving to see a woman at least once, by 3 weeks postpartum especially if she has risk factors like hypertension; and making sure they’re having a continuity of care with their primary physicians.”

Postpartum care should be about more than birth control

For most women, the last few prenatal appointments likely involve some sort of conversation between a woman and her doctor about how she will go about not getting pregnant again—at least not right away. After giving birth, this same conversation will be had between the new mother and whoever helped deliver her baby—from the doctor or midwife, to the nurses who also attended the birth or who are present as the mother and baby are discharged from the hospital. Pregnancy prevention is also a topic that recurs during the 6-week postpartum follow-up visit. In fact, with such a large focus on contraceptive options in the last stages of pregnancy and during the only guaranteed visit postpartum, it can begin to feel like preventing another pregnancy from happening too soon is all that matters in terms of women’s postpartum health.

But, considering how cardiovascular events and mental health-related issues are some of the leading causes of maternal mortality, it is highly problematic that most U.S. postpartum care consists of pushing hormonal contraceptives on women, given all of their known risks to cardiovascular and mental health, when postpartum women are already at heightened risk for these complications. Especially considering that women who are breastfeeding (which the majority of U.S. women do at first) are likely to have a delayed return of ovulation, the U.S. medical community’s prioritization of contraception during the already limited time for postpartum care is doubtful to promote the well-being of new mothers.

That’s where modern methods of natural family planning could better serve women than contraceptives postpartum. If patients are at increased risk of cardiovascular events, for instance, they “could still use Fertility Awareness-Based Methods to space their pregnancies while they’re concentrating on addressing some high-risk medical issues,” Dr. Holmes-Mason told us.

What real postpartum care looks like

In an ideal world, a woman would be guaranteed more than one postpartum visit, and she wouldn’t have to wait over a month to get the care she may desperately need (especially considering that the first 42 days postpartum are the most dangerous in terms of elevated risk). The U.S. medical community should prioritize home visits, as every new mother knows how difficult it can be to get out of the house with a newborn. The content of these visits would be about checking up on the physical health of the new mom, as well as checking in with her emotionally to see how she is handling the transition, and referring her for immediate specialty care if needed.

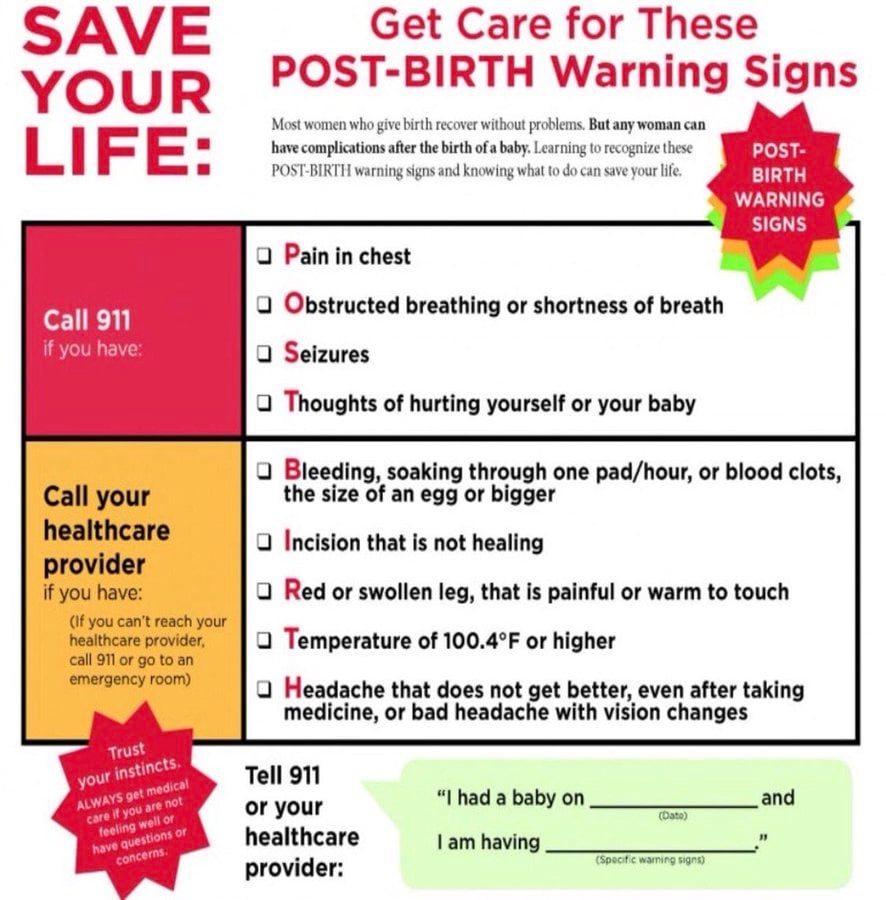

Postpartum visits should also be about educating the new mom about her body, from the potential warning signs she may be receiving (and how to seek immediate care for them if they are especially concerning), and how to watch for the return of her cycle via fertility awareness. Ideally, more healthcare providers would also be knowledgeable about the unique disparities in postpartum health and wellness between white patients and patients of color, and be hyper-aware of the risks that black mothers, in particular, face during the postpartum period. Pelvic floor therapy would also be the standard of care—as it is in France—after a vaginal delivery, in order to prevent urinary and fecal incontinence in the short-term, as well as reduce pelvic pain levels, and—yes—even help them enjoy sex again. Importantly, it also reduces pelvic organ prolapse in the long-term. Even in an ideal world, these visits would not necessarily have to be with an OB or midwife. During the postpartum time, allied healthcare professionals (AHP) like doulas or home nurses can bridge the gap, and provide a great deal of support to a new mother, by informing her what is normal in terms of their postpartum adjustment and healing, and when she may need to seek out more specialized care. Adding this support goes a long way toward combating the overwhelm that many new mothers have—the feeling that they need to “do it all,” whether they are healthy or not.

“We should really try to have a team-based approach while engaging women and their families,” Holmes-Mason says, “not just physicians and nurses but social workers, the use of doulas, midwives, as well, continuing to follow up with women in that postpartum period.”

Holmes-Mason also believes that patients should be regarded as a partner in their own health. “And not use the patient, but her village—her spouse, support people, faith-based community—all of them can be helpful to the woman in helping her care for her and identifying signs that warrant further medical attention.” Holmes-Mason recommends an acronym produced by the group AWHONN that teaches women and their family members about the warning signs post birth, addressing: “when should I be concerned, when should I reach my doctor, when should I go to the ER?”

“These are things it’s important for patients and her support people to be aware of,” Holmes-Mason stresses.

Adding pre-pregnancy care to women’s health

Lastly, to serve the whole person, the women’s health community could benefit from paying greater attention to pre-pregnancy care. “That’s something we’re not focusing on as much,” Holmes-Mason says, “addressing women that have high blood pressure or diabetes before they’re pregnant,” and trying to optimize them for healthy pregnancies and beyond. “I think OB/GYNs do a great job of that but our primary care physicians may not be aware that some women intend to conceive at certain times in their lives,” says Holmes-Mason who thinks pre-pregnancy is “a really great time for women to modify their risk factors.”

She has a point, since family planning should not just be about pregnancy prevention, but also the hopes of patients who want children to prepare them for that as well. To that end, women seeking comprehensive healthcare and a fuller view of family planning can benefit from charting their cycles with Fertility Awareness-Based Methods (FABM), sooner rather than later. These modern methods of natural family planning equip women, with the help of FABM-trained medical professionals, to identify reproductive health disorders as well as general health issues that could obstruct optimal health both now and in the future.

On past International Women’s Days, we at Natural Womanhood have called for an increased attention to fertility awareness and reproductive respect at large for women. In the face of the devastating maternal mortality crisis in the United States, this call could not be more vital.

Correction: A former version of this article included a misquotation on the “coordination of care outside hospitals, from an outpatient setting to a primary care setting”; we apologize for the incorrect transcription of that quotation and have since corrected it to say “inpatient” setting.

Additional Reading

Birth Control After Baby the Natural Way, Technology Assisted

Deciphering the Postpartum Period with Fertility Awareness

Understanding and Recognizing Postpartum Depression

What’s the Best Postpartum Fertility Awareness-Based Method?

Three New Technologies to Revolutionize the Postpartum Period

Three Science-backed Ways to Ease Childbirth and the Postpartum Period

Does Breastfeeding Prevent You From Getting Pregnant?

Good and Bad News Concerning the LAM Method During the Postpartum Period