While much remains unknown about the causes of autoimmune disease, we now know that hormonal birth control is at least partly responsible for the increase in the explosive growth of autoimmune disease diagnoses.

Lupus is primarily a rheumatic disease. Multiple Sclerosis attacks the central nervous system. Crohn’s disease goes after the gut. Despite the differences in the broad scope of diseases that fall under the autoimmune disease umbrella, there is evidence of a robust underlying bond. One in every four autoimmune patients will be diagnosed with another autoimmune disease, and each of these diseases is the product of a renegade immune system attacking the body’s healthy tissue. But the connection expands beyond what’s been labeled as multiple autoimmune syndrome.

The autoimmune disease and estrogen connection

During his studies of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in the late 1950s, Dr. Noel Rose first theorized the idea of the body’s immune system attacking itself and came up with the term “autoimmune” that would lead to him being deemed the Father of Autoimmune Disease. Dr. Rose believes that researchers have known from the beginning that estrogen plays a critical role in autoimmunity because of the role it normally plays in a woman’s immune system, plus the fact that nearly 80 percent of all diagnoses were (and are) women.

Dr. Rose believes that patients must be genetically predisposed to contract an autoimmune disease, but stresses that environmental triggers are the real key to activating the condition. Studies of identical twins have demonstrated that autoimmune diseases only strike both twins 24 percent of the time. If an autoimmune disease were purely genetic and attacked one twin, by its very nature, it would also strike the other sibling. Since that does not always happen, environmental factors must play a role.

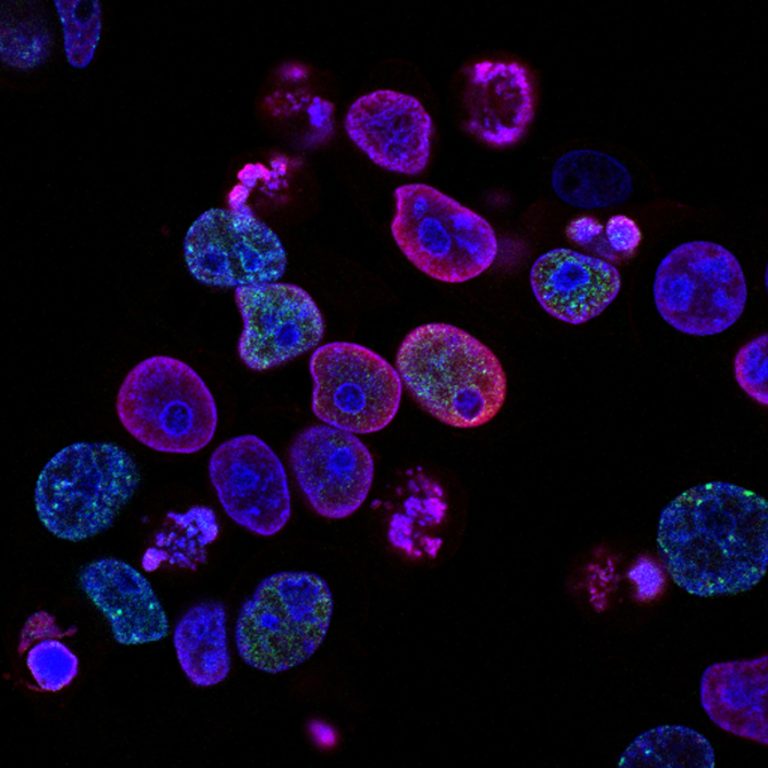

Dr. Rose has described the body’s T cells as the soldiers of the immune system. He says that when our body’s natural estrogens attach to receptors on these T cells, it arms the soldiers and gives them their marching orders. Natural estrogen basically points out the invader and triggers the command to attack. But when disruptive agents that mimic natural estrogen enter our body, they attach to the receptors. Suddenly, the soldier is armed but doesn’t know what to attack because the synthetic estrogens don’t carry the code our natural estrogen would have provided. This can cause the armed immune system to battle our body’s healthy tissue, which may result in an autoimmune disease for those who are genetically predisposed.

The bad news is that many people are genetically predisposed. In the United States alone, more than 23 million people suffer from an autoimmune disease. Collectively, their incidence is higher than that of cancer or heart disease.

Birth control is an endocrine disruptor

The disruptive agents that mimic estrogen in our bodies are known as endocrine disruptors, and they’ve gained a lot of notoriety in recent years. News stories in the mainstream media frequently focus on disruptive chemicals such as dioxins, detergents, BPA, even soy. Unfortunately, discussions of endocrine disruptors rarely include the most prolific and potent synthetic chemical explicitly designed to mimic natural estrogen in the body—hormonal birth control.

A conservative estimate of 19 million women in the United States ingest or are using some form of hormonal contraceptive each day. Given that each molecule of those synthetic estrogens is about 100 times more potent than a woman’s natural estradiol, birth control equates to a powerful form of internal pollution—a physician-prescribed endocrine disruptor. But, how can we be certain they are any more to blame for the rise of autoimmune diseases than of the other chemicals known to disrupt the endocrine system?

The first indication is that the incidence of autoimmune diseases has risen dramatically since the introduction of the Pill. One could argue that many other harmful chemicals were introduced into the environment within the same timeframe, and that’s a valid point. But it doesn’t explain the fact that the gender ratio has also skewed dramatically since the Pill was introduced. For example, twice as many women as men were diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) in 1940. By 2000, four out of five MS patients were women. That’s a 50 percent increase over each decade since the Pill was introduced.

Some research suggests women who used or use birth control are more likely to develop multiple sclerosis, lupus, and Crohn’s disease.

What we know about hormones and autoimmune disease

In the grand scheme of things, scientists still understand very little about the inner workings of autoimmune disease. This we do know: hormones are powerful chemical messengers that play a role in just about every process our bodies perform. Even though we don’t know precisely how these messengers work or exactly what their role is in the immune system, we should know enough by now to try not to throw them out of balance.

References

Click a subtopic below to view scientific references for each of the following autoimmune diseases and their connections to birth control use.

This page was last updated on April 26, 2024.

For more information on autoimmune diseases, see the articles below.