“I’m terrified of pulling my ACL today,” my teammate and lifting partner in college told me while stretching on the gym floor. In between reps, we talked about an article she recently read about how women are more prone to injury during specific phases in their menstrual cycle.

Until then, I had no idea there was a “better time” to go for a PR (personal record) or a “bad time” to strain yourself physically. Day one of my period was a skip day. Any day before or after that was fair game! But as a recent study on British female soccer players (“footballers,” to our friends across the pond) indicates, there is a wealth of information to be gleaned from research on female athletes and their injuries and performance during various phases of their menstrual cycles [1].

Are you more likely to get injured during your period?

Unsurprisingly, as more women participate in sports and strength training, the demand for data on how the menstrual cycle affects physical performance also increases. For example, you’ve likely noticed the recent spike in popularity of practices like cycle syncing on social media.

While proponents of cycle syncing often advocate for resting from strenuous exercise (when possible) during your period, the surprising new study published in the journal of Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise found that your risk of injury may be higher during the phase preceding your period (i.e., the luteal phase) than during your period [1]. The study, which followed 26 female professional soccer players over a 3-year period, found that “players were six times more likely in the pre-menstrual phase and five times more likely in the early-mid luteal phase to experience a muscle injury” compared to when they were on their periods, according to a press release for the study. Players were 2.3 times more likely to experience injuries of any kind (not just muscle injuries) during their premenstrual phase (14 injuries per 1000 person-days) compared to during menstruation (6.1 injuries per 1000 person-days).

The study, which followed 26 female professional soccer players over a 3-year period, found that “players were six times more likely in the pre-menstrual phase and five times more likely in the early-mid luteal phase to experience a muscle injury” compared to when they were on their periods.

Interestingly, other research has shown that you may be more likely to tear your ACL, in particular, right before ovulation (i.e., the follicular phase) [2]. But during the luteal/premenstrual phase directly before your period (the time when you may feel moody, bloated, and/or fatigued), your risk of muscular injury may be highest. (Notably, researchers relied upon a calendar-based algorithm to determine which phases the players were in during their various injuries, instead of biomarkers of fertility—more on why this is problematic in a bit!).

Injury risk is tied to estrogen levels

How could workout injuries be menstrual cycle-related? Why might women be more prone to muscle injury during the leadup to their periods? While progesterone and relaxin play supporting roles, it turns out that injury risk in women may have much more to do with their estrogen levels [1][2]. This is because estrogen greatly affects the function of your musculoskeletal system, meaning your muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bones. And the difference in injury during each one can be profoundly different, because from the beginning of your cycle until ovulation, estrogen increases 10-100 fold [3]!

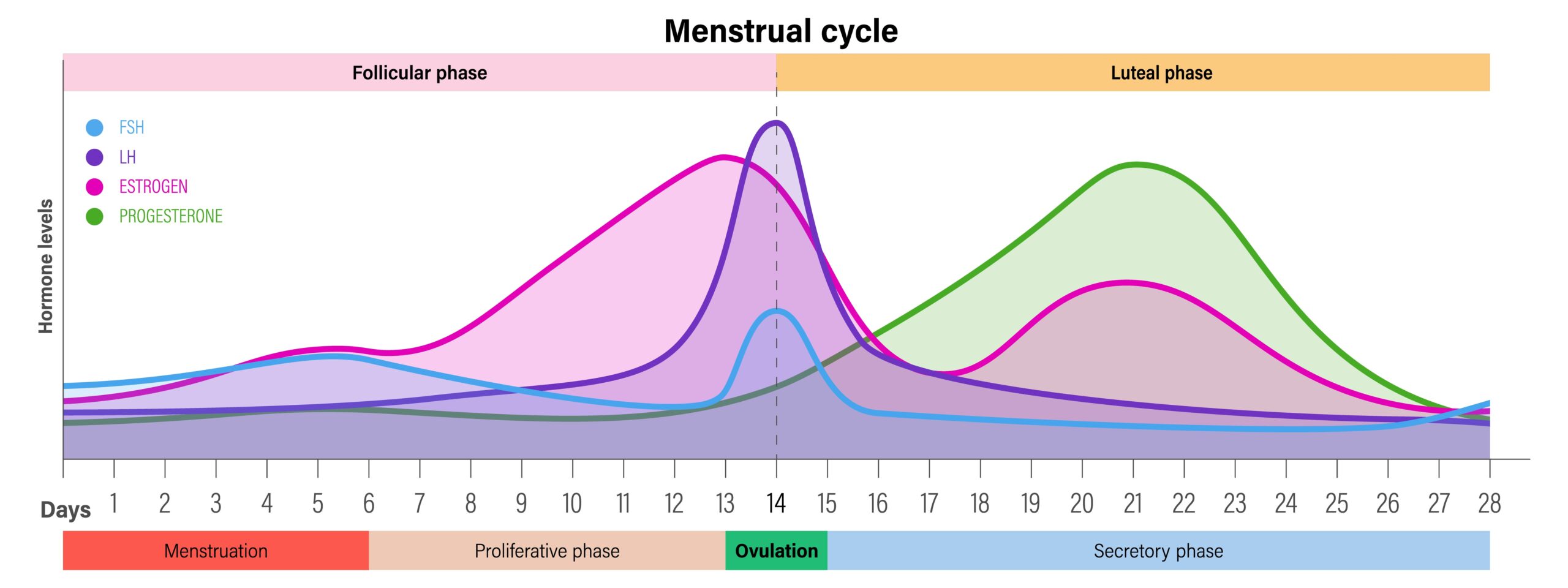

To understand the connection between injury risk and menstrual cycle phases, there are three key phases to consider (follicular, ovulation, and luteal), and the most important question during each one is: How high (or low) is your estrogen?

When you start your period at the beginning of your cycle, your estrogen and progesterone are both low. Estrogen gradually increases throughout the follicular phase, until it peaks around ovulation, roughly mid-cycle (while your progesterone remains low). After ovulation, your estrogen begins to decrease, while progesterone begins to increase. Estrogen picks up again briefly during the luteal phase, but after progesterone peaks towards the end of the luteal phase, both hormones drop precipitously towards the end of the cycle, triggering your next period (and a new cycle).

How could high estrogen help your bones and muscles, but endanger your tendons and ligaments?

Estrogen simultaneously improves bone function, builds muscle mass, and reduces tendon and ligament stiffness. Relatively stiff ligaments are actually favorable for strength training because they maintain better joint stability than lax or loose ligaments. Loose or lax ligaments are more prone to tearing, which explains why we see an increase in ACL tears during the time when estrogen peaks (i.e., around ovulation!).

On the flip side, tendons that are “too stiff” strain the muscles and force them to stretch and compensate for the lack of flexibility. This may cause muscle injury, like pulling a hamstring or groin muscle–which is probably why we see an increase in muscle injuries during times when estrogen is lower, like during the premenstrual period!

The presence of estrogen may also explain, in part, why women are generally more likely to suffer anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears than men, but less likely to experience muscle injury [4].

Why is much of the data on menstrual cycles and female athletes potentially unreliable?

Now, a brief caveat. Remember that calendar-based algorithm we mentioned that the 2024 British study used to determine the female athlete’s cycle phases during their injuries? It means we need to take these results–and most results concerning studies on female athletes and the menstrual cycle–with a grain of salt, and here’s why: As this meta-analysis reflects, much data on female athletes and the menstrual cycle comes from similar estimates of where participants were in their cycles, which essentially amounts to using the outdated, unreliable Rhythm Method [5].

The Rhythm Method is a calendar-based method of period tracking, which assumes a woman’s various cycle phases start and stop on particular days of a “standard” 28 day cycle. Interestingly enough, recent data from Natural Cycles, a fertility awareness app with over 2.5 million users worldwide, found that the average length from 600,000 cycles was not 28 days, but 29.3 days!.

Calendar-based methods of tracking a woman’s cycle are therefore notoriously error-prone, because many women have longer or shorter cycles than 28 days, and cycle length can vary from one cycle to the next due to factors like illness, stress, etc. In other words, if a woman is participating in a research study during her luteal phase but researchers believe, based on calendar-based algorithms or estimates, that she’s still in her follicular phase, their results will be inaccurate.

What would it take to ensure accurate cycle data?

In order to be considered reliable, data on the menstrual cycle and female athletes should confirm where each participant is in her cycle using various biomarkers of fertility, or various testing like urinary ovulation detection kits and/or blood samples to confirm menstrual cycle phase [5][6]. Preferably, both would be used!

While this doesn’t entirely discount the results of the British soccer player study (or other studies like it), we need to be careful with assuming they’re the final word in how the menstrual cycle affects female athletic performance. This is a good start, but better, more detailed research is needed!

The bottom line

The cycle of estrogen-related stiff tendons and strengthened bones as described above is natural in premenopausal, naturally cycling women (i.e., women who are not on hormonal birth control).

Dr. Jo Blodgett, one of the researchers for the 2024 British soccer player study, observed that much more cycle information is needed, and that studying much greater numbers of women is key. “To better understand the variability in injury risk across the cycle we need more players and teams to continually track injury incidence, menstrual cycle and symptoms in a standardised manner.” Again, we would also add that studying women’s cycles using biomarkers of their fertility (and not just calendar-based estimates of cycle phases) is essential to good research surrounding the impact of the menstrual cycle on female athletic performance!

Certainly, female professional athlete teams stand to benefit a great deal from such careful research, since “at the elite level, injuries to your squad can mean the difference between winning and losing, the difference between being crowned champions and runners-up.” But most crucially, “it means pain and suffering for players that could perhaps be avoided with better player-centred support.” We couldn’t agree more!

Additional Reading:

Do female athletes perform worse during their periods?

Knee surgery, blood clots, and birth control: The risks young female athletes need to know about