“Ever wonder why childbirth is the most profitable hospital procedure? Or why it is a hospital procedure at all?” So writes Allison Yarrow in her book, Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men over Motherhood. With gripping detail, sympathetic prose, and— at times— righteous anger, Yarrow offers a compelling critique of the medicalization of pregnancy, birth, and motherhood While her approach is lacking in some ways, we cheer on her efforts to showcase the beauty and raw power of birth and motherhood. In this Natural Womanhood book review of Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men Over Motherhood, we cover its strengths and limitations and offer our recommendation on whether to buy, borrow, or pass.

Allison Yarrow is an award-winning journalist and has written for outlets such as The Washington Post, The New York Times, Vox, and Elle. She has given TED talks and appeared on multiple shows, speaking about birth and other women’s issues. As she notes in the introduction, she conducted extensive research for Birth Control over the span of many years, interviewing a wide variety of doctors, midwives, birth workers, and patients. She also draws on her own experience as a mother of three— two of whom were born in the hospital and the third of whom was born at home.

Who is the intended audience?

Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men Over Motherhood’s primary audience is women, although anyone who is interested in women’s issues would find the content in the book to be compelling (granted, some men may be put off by the accusation implicit in the subtitle). Yarrow says she also intended the book for “trans men” and “non-binary people” (i.e., biological women, all).

What are the main content areas of Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men over Motherhood?

Yarrow’s book is a mixture of historical background, interviews with medical professionals, summaries of research and scientific studies, insights from surveys and interviews conducted with individual women who underwent pregnancy and birth, and her own personal experience. She discusses misconceptions and fears in pregnancy, current medical practices in childbirth and why they exist (for example, the mistaken belief that many women’s pelvises are too small to give birth, and hence, why early induction or C-section is often recommended for a “big baby”), difficulties that arise in the aftermath of childbirth, and the beauty of home birth.

Strengths of Birth Control: The Insidious Power of Men over Motherhood

Yarrow really shines in her research. She investigates each issue deeply, gleaning evidence from multiple sources and showing again and again how many common medical practices in obstetrics are scientifically questionable or carried out in unethical ways.

She makes the argument that very few C-sections are medically necessary

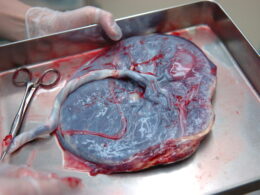

I especially appreciated her chapter on C-sections, titled “Surgical Strike.” I was particularly interested in this chapter because I am currently expecting twins, and many twin birth stories end in C-sections. Naturally, I’ve been curious whether the C-section rate for twins is justified, and, more generally, whether the rising cesarean rate is really a cause for concern.

Here’s what Yarrow has to say:

“C-sections are absolutely needed, according to [Neel] Shah, [an OBGYN at Harvard who has performed thousands of C-sections], in a few rare scenarios that endanger mom and baby: placenta previa, when the placenta covers the cervix; vasa previa, when fetal blood vessels move into the uterus, putting it at risk of rupture; and umbilical cord prolapse, when the umbilical cord drops into the vagina and blocks the baby’s exit. These needed C-sections make up only about 4 percent of the total. The other 96 percent are, by Shah’s definition, unnecessary” (Yarrow, 121).

Yarrow goes on to discuss how C-sections increase the risks of the leading causes of maternal mortality, and additionally can disrupt mother-baby bonding, make breastfeeding difficult, and cause longer and more painful healing for the mother. She then deftly weaves two stories from individual women into her narrative – one detailing a more typical traumatic cesarean and one describing a “gentle C-section.” I found her description of the traumatic C-section powerful:

“LaToya remembers the oxygen mask pressed to her face, occluding her vision, and the shock of being strapped down, then the stupor. Her arms and wrists were glued to the table. Nearly all the women I’ve talked to about their C-sections recount this detail – being chained to the table – how powerless and abused they felt, how no one told them about that part before it happened or explained why when it did. LaToya described it as being bound, like on a cross” (Yarrow, 137).

She draws on individual birth stories to communicate universal themes

Yarrow is also at her best when she is relating personal stories, like the ones mentioned above or even her own birth stories. The story of her home birth likely will give many women the desire to have an experience just like that, where they “feel the most power [they’ve] ever felt” (Yarrow, 259) because they are allowed to birth on their own terms and in the peace and comfort of their own home. And this, as Yarrow says at the end, is something she believes all women deserve to experience.

Limitations or Blind spots

Yarrow fails to give mothers their due

I knew from the first page I would have some disagreements with the author. First, although she acknowledges that “Not using [the terms] woman and mother could be considered its own form of misogyny” (Yarrow, ix) – which I happen to agree with – she goes on to note how she will use the term birthing people to include those who give birth but do not feel like they are women. This decries the very real experiences of those women who see pregnancy, birth, and mothering as the full embrace of their own biological womanhood. I also thought it a non sequitur that in the same introduction, she laments the collapse of Roe v. Wade as the fall of a “fundamental human right to abortion,” forcing women to relinquish “control” of their bodies (and thus failing to account for the reality of preborn babies’ bodies, or to acknowledge that one person’s rights end where another’s begin).

Yarrow misses an opportunity to make a connection to hormonal birth control and the broader medicalization of women’s fertility

Yarrow had a prime opportunity to connect the dots between the medicalization of pregnancy and birth, and the broader medicalization of women’s fertility via hormonal contraception. Birth control shuts down a woman’s natural cycles, effectively treating her body’s normal hormonal patterns as public enemy #1. Might a woman who has accepted the premise that fertility must be altered, suppressed, or destroyed with birth control (to paraphrase Leah Jacobson) be less likely to push back against insinuations from the same medical experts who prescribed her the Pill that she must have her labor and birth medically managed, too?

Given the title, I expected Yarrow to discuss the birth control pill more deeply and how detrimental it has been to women’s health in the past century. To her credit, Yarrow does spend a few pages relating birth control’s side effects, and she notes how it is overly prescribed with no opportunity for real consent given on the woman’s part. I was also gratified to see a mention of Lisa Hendrickson-Jack, with a nod to fertility awareness. But then Yarrow, in describing her college experience, merely labels her previous desire for the Pill as a product of “patriarchal conditioning.” But how could the pill be exclusively a tool of the “patriarchy” when it was the brainchild of one woman (Margaret Sanger, founder of Planned Parenthood), and bankrolled by yet another woman (Katherine McCormick, who “provided almost every single dollar necessary to develop the oral contraceptive”)? Yarrow fails to unpack any of those questions.

A lot gets blamed on “the patriarchy”

This brings me to my last disagreement with Yarrow: the overuse of the term “patriarchy.” I found the “systemic patriarchy” explanation for everything – from the birth control pill, to interventions in birth, to shame in breastfeeding – to be an incredible oversimplification. Frankly, by Chapter 9 (the chapter on breastfeeding), it got repetitive.

Such a rote explanation leaves no room for discussion of the complex causes behind the many failures in women’s healthcare, such as the rise of hormonal birth control, the emphasis in the feminist movement on women being “liberated” from the home and childbearing, or the couching of abortion as a woman’s fundamental right. In reality, all of these have created such a great wedge between the mother and child, that women themselves have become less connected with their basic maternal instincts and more willing to embrace hospital procedures that are often unnecessary or even damaging.

On a practical note, I found myself wondering how the patriarchy can be completely to blame when the vast majority of obstetricians and birth workers are now women? Yarrow seems to fall short here with this explanation, and I wish she utilized her skills as a journalist and researcher to investigate these deeper issues.

She might throw the baby out with the bathwater

Yarrow makes a strong case for the manifold ways the medicalization of pregnancy, labor, and birth has been to the detriment of women and their children. At the same time, at present the vast majority of women continue to give birth in a hospital setting. A hospital birth that respects the woman’s body and ability to labor without interventions and on her own timeline is possible, but how many readers of Birth Control would know that?

The main focus of the book seems to be to increase awareness of the issues in women’s health, especially as they pertain to birth, rather than to offer practical solutions for them. Women will find the research and sometimes horrific details of what can go wrong in women’s healthcare and during hospital-based births eye-opening. The average woman who is pregnant or considering pregnancy will likely be made aware of her need to do her own research, to boldly advocate for herself— particularly in a hospital setting— and to choose what she truly thinks best for herself and her preborn baby.

I am not sure that most medical providers would pick up a copy of this book, but if they did, they might receive the most impetus to change what Yarrow calls the “patriarchal system” in healthcare, and to consider whether the medical model they follow is truly in the best interest of the women they serve.

The verdict: to buy, borrow, or skip altogether?

I think Birth Control is worth the read for those who are interested in women’s health or for women who are considering pregnancy. It leaves no stone unturned in detailing women’s options during pregnancy and birth. Many women will find it helpful to see the “why” behind so many birth interventions, so that they can make truly informed choices for their own health and their babies’ health. I would borrow, not buy, due to the book’s limitations and repetitiveness. Those who want much of the same information without committing to the reading time may do well to just simply watch The Business of Being Born!

Additional Reading:

The 6 things every woman considering a natural childbirth needs to know

Traumatic birth experiences are more common than you think: A mental health perspective

Surgeons benefit from upselling. Planned c-sections often come with an offer of tubal ligation “while we’re in there.” A friend told me she regretted her tubal ligation (scheduled into a planned c-section) within a week. She had felt heavy and overwhelmed in the 3rd trimester and made the choice at a vulnerable time.