The morning I went to the hospital for my scheduled C-section, I received a stack of consent paperwork to sign regarding the risks and benefits, anesthesia, stitches, and how they would dispose of my placenta after birth. I think this was the first time I ever heard the placenta referred to as an “organ,” and it kind of blew my mind.

In fact, I think I was surprised because it was the first time I had given my placenta much thought at all. Yet, the placenta is an incredible and fascinating (temporary!) organ grown in a woman’s body for and by another person. So, today, let’s learn a few facts about the amazing placenta.

Where does the placenta come from?

Around 9-10 days after conception, the blastocyst (the scientific name for your baby during days 5-12 after conception) implants in the endometrio (the lining of your uterus). At this point, the cells of the blastocyst that will eventually become the placenta have “differentiated,” meaning that they’ve separated themselves from the cells that will become the baby. Until they finish forming, though, the endometrium envelops, and provides nutrients to, the growing blastocyst directly [1].

The mother’s body makes progesterone until the placenta is ready to do so

During this time, the mother’s body is directly connected to a poppyseed-sized baby who’s doing the incredibly hard work of growing his or her own body from scratch. The mother’s cuerpo lúteo (remember that the corpus luteum is the ‘leftovers’ after the follicle burst at ovulación) produces progesterona to sustain the pregnancy until the placenta develops enough to take over that job. This occurs around 12 weeks.

The placenta makes “the morning sickness protein,” GDF-15

The placenta isn’t sólo responsible for progesterone production, however. The placenta also makes a protein called Growth Differentiation Factor 15 (GDF-15) to support the growing baby. Interestingly, GDF-15 has been linked to nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, colloquially known as náuseas matutinas. Women have different baseline levels of GDF-15 when not pregnant, and those with a lower baseline or higher sensitivity to GDF-15 may develop hyperemesis gravidarum, while the rest of us will more likely see nausea symptoms subside by the second trimester [2].

What does the placenta do?

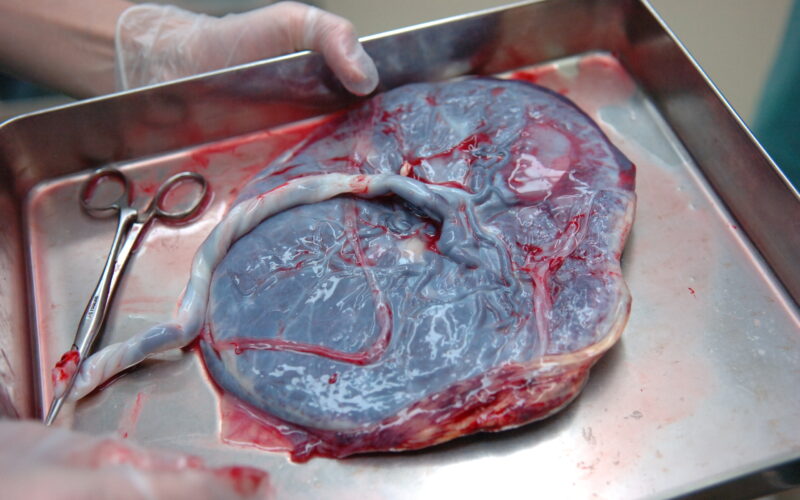

By the end of pregnancy, the placenta grows to about 9 inches wide and 1 inch thick, and weighs about 1 pound (for reference, that’s roughly the size of your standard dinner plate!). The placenta’s maternal side, called the decidua, attaches to the endometrio and prevents the mother’s body from rejecting the baby as a foreign invader [3]. This side connects directly to the mother’s bloodstream.

The fetal side of the placenta, called the chorion, is formed by the blastocyst’s own cells and connects through the umbilical cord to the baby’s bloodstream. A typical, healthy umbilical cord has two arteries and one vein. (Note that a rare anomaly with only one artery can present increased risks to the baby’s growth.)

The placenta functions a lot like a dialysis machine, processing the baby’s blood and performing five main jobs [4]:

- Respiratory: While the baby cannot breathe air in utero, oxygen from the mother’s blood passes directly into the baby’s blood, and carbon dioxide passes the other way.

- Excretory: Before the baby’s own kidneys can clean their blood and make urine, the placenta does the work for them.

- Nutrition: Glucose and micronutrients pass from the mother directly into the baby’s bloodstream.

- Immunity: The baby receives antibodies from past and current infections, protecting them from anything the mother might catch while pregnant, as well as offering some protection from things the baby might be exposed to during and immediately after delivery.

- Endocrine: The placenta makes hormones like hCG, progesterone (mentioned above), estrogen, and lactogen to sustain and support the baby’s development.

How to grow a healthy placenta

Research reveals the role ambos parents’ preconception health plays in their child’s health, in utero and beyond. In fact, both Dad’s and Mom’s preconception health may también impact Mom’s pregnancy health. You read that correctly! We now know that the Dad’s DNA drives the gene expression in the baby’s side of the placenta. His diet, lifestyle, and gut microbiome have an epigenetic impact (differences in how genes are expressed based on environmental influences) on placental health y impact maternal risk of preeclampsia.

Of course, Mom’s nutrition and exercise also promote healthy placental development. Exercise in particular promotes the production of blood vessels in the placenta, and stimulates Placental Growth Factor (PGF), potentially decreasing her risk of complications like preeclampsia further into her pregnancy.

Where the placenta implants may affect your ability to feel fetal movement

If the placenta happens to implant in the front part of the uterus, this is called an “anterior placenta.” It’s absolutely safe, but it can make fetal movement harder to detect. Typically, mothers with anterior placentas will feel “quickening” (a baby’s first fluttering movements) later than they would with the placenta in the back. Movements can also just feel different. Case in point: I myself had an anterior placenta with my 2020 baby, and for the entire pregnancy, her kicks registered in my brain as hunger pangs, even though I knew it was her!

Placenta problems

Sometimes the site of the placenta’s implantation can be a real problem. If the placenta completely covers the cervical opening, called placenta previa, safe vaginal delivery is impossible due to hemorrhage risk. Healthcare professionals will monitor you for bleeding and scheduled for a C-section delivery, usually at “early term” (around 37 weeks). If the placenta partially covers the cervix, there’s a little gray area in terms of vaginal vs Cesarean birth. Your healthcare professional will discuss risks and benefits with you.

Additionally, if the placenta implants too deeply in the uterine wall, such as can occur due to scarring from a previous C-section, women may hemorrhage after vaginal birth. Fortunately, 20 week “anatomy scan” ultrasounds can detect if the placenta is embedded too deeply so that a plan can be made for a Cesarean birth.

If you’re attempting a trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC), you’re at a slightly increased risk of placental abruption, detachment of the placenta from the uterus antes de the baby is delivered. Placental abruption is a life-threatening emergency for both mother and baby and requires an immediate C-section.

Preeclampsia

A more common placenta-related concern is preeclampsia, which has been tied to placental development issues causing maternal high blood pressure. Preeclampsia causes hypertension, liver and kidney damage in the mother and, if it progresses, stroke (at which point it’s known as full-blown eclampsia). It’s a serious condition that usually requires early delivery to resolve.

As we have discovered that the father’s DNA impacts the healthy development of the placenta, men’s lifestyle choices may help decrease the risk of their partners contracting preeclampsia in the first place. Fascinatingly, some research suggests that regular pre-pregnancy exposure to the same man’s semen can help prevent preeclampsia during pregnancy with his baby.

Mortinato

A 2024 study at Yale examined 1,256 placentas from previously unexplained stillbirths (pregnancy loss after 20 weeks gestation) and determined that the majority of these tragedies were caused by placental defects [5]. Read this article to learn why Yale researcher Dr. Harvey Kilman encourages all women to ask their doctors to take three specific placental measurements during their routine ultrasounds. It might save your baby’s life!

The placenta is birthed after the baby

After you deliver your baby, either vaginally or surgically, you will deliver your placenta as well. Once the umbilical cord has delivered the last of the baby’s blood back into his body, it will be clamped and cut, and among the various checks and procedures performed on both you and your baby, the doctor will perform a quick examination of the placenta.

Retained placenta is the primary placenta problem that can occur after birth [6]. If the placenta comes apart during delivery, and some is left inside you, it’s crucial to remove the fragments before they cause life-threatening infection or hemorrhage.

What to do with the placenta

Once your placenta is delivered and inspected, you don’t have to consent to the hospital disposing of it as medical waste like I did with mine. In fact, there are reasons you might want to keep it.

Placentophagy or placenta encapsulation

The practice of consuming the placenta, called “placentophagy,” has been growing in popularity in the West since the 1970s. A 2018 literature review noted, “We found that there is no scientific evidence of any clinical benefit of placentophagy among humans, and no placental nutrients and hormones are retained in sufficient amounts after placenta encapsulation to be potentially helpful to the mother postpartum” [7].

Still, some claim consuming your placenta can rebuild your depleted nutrient stores and help prevent mood disorders like postpartum depression. Placenta encapsulation services dehydrate your placenta for you for easy ingestion during the postpartum period.

Donation to science

Placentas can also be donated, either for research, or even as donor tissue. The placental membrane has documented usefulness in eye surgery, reconstructive surgery, burn treatment, and wound dressing. More on how to donate your placenta is aquí.

Lotus birth

Some families and cultures choose a “lotus birth” (also known as umbilical nonseverance) where the entire cord and placenta are kept attached to the baby until they detach naturally. This is believed to be a gentler transition to life outside the womb, and to respect the baby’s ownership of the placenta. Robust studies have not yet been done to determine the medical risks and benefits of this practice, but there are preocupaciones that the dead tissue of the attached placenta could potentially lead to an infection. There are many considerations involved in planning a lotus birth, including preservation and storage options, so do your own research if you’re interested.

Cultural practices around placenta disposal

Others, such as the Maori and Cambodian cultures, bury the placenta in the ground. I know a friend who planted a tree over hers in her backyard. Still others use their placenta to make one-of-a-kind art pieces or jewelry.

Lo esencial

This hard-working but transitory organ is a small but mighty nutritional, oxygenation, and waste removal lifeline for a growing baby, and may even have value after the baby’s birth. While things can (and sometimes do) go wrong during placental development, we learn more every year about the impact both mom and dad’s pre-pregnancy health and wellness can have upon these various issues. I now understand why the placenta warranted its own consent paperwork when I had my C-section!